It’s a question that has certainly plagued more than one country: What do we do with statues and plaques that are part of a history we do not want to honor?

Hungary has a tortured past, both literally and figuratively. Setting aside everything before the 1900’s, which is a lot of complicated history, Hungary lost 2/3 of its territory in the aftermath of WWI. To make a long story short, Germany helped restore most of that territory, forcing Hungary into Germany’s grip as WWII started.

At one point, Germany demanded that over 200,000 Hungarians fight the Soviets on Soviet soil. Outnumbered and ill-equipped, ¾ of those who fought were killed, starved, frozen, imprisoned, and never came home. In the meantime, Germany found like minds in a Hungarian group, the Arrow Cross Party, and their atrocities against the Jews and others took countless more lives, to the point that when the Allies won the war and Russia was given control over Hungary, many Hungarians welcomed them.

The welcome was short-lived. Russia quickly clamped down on Hungarian life. Over the next 40 years they not only oppressed, tortured, murdered, imprisoned and otherwise controlled Hungarians’ lives, they also quickly created their own spin on history and erected monuments and other public displays to celebrate their great leaders and their heroic fighters.

After deadly uprisings and lots of political maneuvering, to say nothing of problems internal to the Soviet Union, by 1990 the Russians had left, and left behind their monuments.

Not surprisingly, Hungarians weren’t excited about having monuments to their oppressors standing tall in public places. After considerable debate and disagreement over what to do with them, a park was created south of Budapest where they could be displayed for educational purposes, and to remind the populace of what had been the most recent source of curtailed freedoms. “Memento Park.”

We wanted to see the park. Having advanced in our understanding of how the metro app works, Nora efficiently guided us down there by tram and bus, winding through increasingly beautiful neighborhoods for 45 minutes along the way.

It’s a beautiful setting. If one didn’t know the reason for its existence, one wouldn’t guess. Sculptures and bas reliefs have been moved into positions surrounding large open circles. Each is fitted with a small plaque saying what it is, although in many cases that wasn’t terribly informative. We looked up some names. Others we have in pictures to look up later.

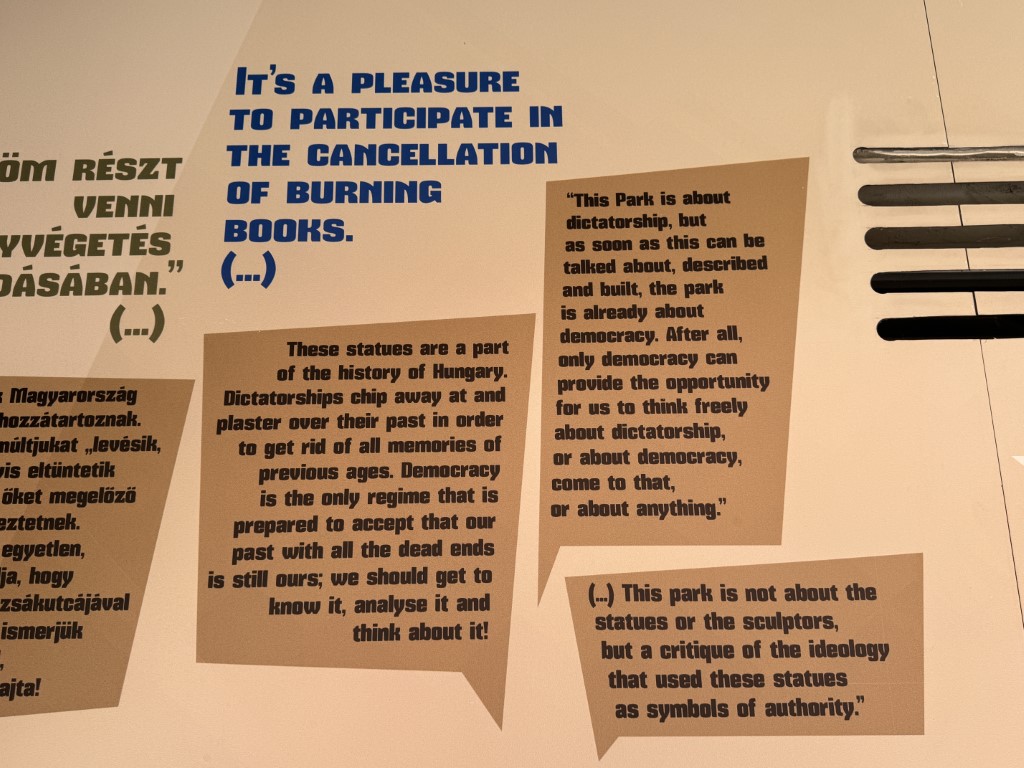

When entering the park, visitors are greeted with a presentation of profound quotes:

“These statues are a part of the history of Hungary. Dictatorships chip away at and plaster over their past in order to get rid of all memories of previous ages. Democracy is the only regime that is prepared to accept that our past with all the dead ends is still ours; we should get to know it, analyse it, and think about it.”

“This park is about dictatorship, but as soon as this can be talked about, described and built, the park is already about democracy. After all, only democracy can provide the opportunity for us to think freely about dictatorship, or about democracy, come to that, or about anything.”

“This park is not about the statues or the sculptors, but a critique of the ideology that used these statues as symbols of authority.”

“In Hungary, as in the other Soviet-occupied Eastern European countries, the new Communist political regime needed its own ideals, mindsets and heroes who could be presented to young people as role models: people whose destiny, legacy and example could bond the people into revolutionary unity. The main aspect for turning previously almost unknown people, deservedly or undeservedly into ‘new stars’, was not what they did in their lives, but how much they were useful for the propaganda purposes of the communist system after their death.”

“The grandstand is a full-scale replica of the dais on which the 8-metre-tall bronze statue of Stalin, Soviet Party Secretary, Head of State and General stood. When the people rebelled against the communist oppression on October 23rd 1956, a crowd sawed the statue off at the knees and pulled it down. During the days of the revolution, the boots, that were all that remained, became a mockery of the dictator. The copy of the pair of boots is a reminder of the inevitable fall of dictatorships of all-time.”

One of the things that baffles older Hungarians is how so many people are leaning toward Russia and away from western democracy. To the older people, the sordid history is very present in their memories, and they don’t believe the leopard has changed its spots.

I walked away from Memento Park once again pondering the perplexities of human nature. How humans could be so cruel to other human beings, by the hundreds of thousands or millions. How some people have the courage to face inevitable loss of privileges, torture, loss of life, loss of everything they own in order to have freedoms restored. How we so often fail to learn from history, cycling through the worst of it again and again. How much we will give up in order to have someone manage our lives, regardless of the cost.

The sky alternated between bright sun and thick dark clouds. It seemed a rather appropriate metaphor for Hungary’s history, and for pretty much anyone else’s.